Nomination Background[]

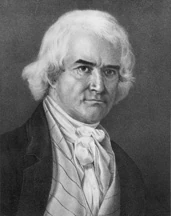

Oliver Hazard Perry, Prime Minister of the URAS

Over the last four years, the Whig Party had suffered several major defeats. Riding high after a succesful administration under Hunter DeRensis, the Duke of Winterfell, they had felt confident in the 1832 Appointment. That was until it was revealed that their Viceory nominee Willie P. Mangum was involved in the death of a North Carolina Governor, and accusations were thrown that their nominee, Joseph Story, had connections to organized crime. The ticket suffered a defeat, Crown Oliver Hazard Perry had become the new Prime Minister, and the Crowns had taken a large majority of Congress. Once officially into office, Perry had several Whigs arrested on "corruption charges" and publically suppressed free speech (most famously in the condoned civilian destruction of the pro-Equality Party newspaper The Liberator in 1832, where no charges were brought upon the perpetrators). Under Lord Secretary of the King's Law, Levi Woodbury, the Royal Bill of Rights were rarely enforced by the government. During this time, King Andrew remained silent on these actions, and only a congressional alliance with the moderate Crowns had blocked Perry from fully repealing the Royal Bill of Rights. He called the document "a direct insult to the responsibility and level-headedness of King Andrew, caused by the Whig Party who would wish to hinder the very base of the monarchy." Because of Perry's radicalism, a noticable schism had occured in the Crown Party, humanized in the form of lifetime moderate Crown, former Secretary of the Treasury, and current Minister of Congress Richard Rush announcing himself a Whig in 1834, taking roughly a third of the Crown's support with him. Since 1832, the Whigs had undergone a political transformation; with most of their original platform enacted, and charges of corruption coming from the other side, former Prime Minister Hunter DeRensis, the undeniable leader of the Whig Party, had written up a new platform, placing civil service reform as one of the key planks. He coined this act as the "Whig Reformation." Many considered 1836 to be one of the most important appointments in the countries history, and for the Whig Party, it most likely meant the key to survival or extinction. They had to defeat Perry and the Absolutist Crowns.

Candidates[]

There were a lot fewer candidates for Prime Minister than there were in 1832, although most observers considered them to be equal in their chances of gaining the nomination. The candidates were:

- Former Lord Secretary of the Army Lewis Cass (53) of North Ontario

- Minister of Congress Hunter DeRensis (57) of Pennsylvania

- Congressman Theodore Frelinghuysen (49) of New Jersey

- Philadelphia Lord Mayor George M. Dallas (44) of Pennsylvania

Lewis Cass, leader of the "Constitutionalist Crown" movement of the early 1830s

Lewis Cass had been a Crown Party member his entire life. He had served with distinction as a Brigadier Colonel in the Second Seven Years War, and had earned the King's favor. For this, he became the first Governor of North Ontario (formerly southern Canada) when it had become a state in 1812 (from 1809-1812 it was under military occupation), and had been an able administrator of his adopted state. Cass had always been a moderate Crown, and open to working with the Whigs to further the country's health. For this reason, he had been offered and accepted the position of Lord Secretary of the Army in the cabinet of Hunter DeRensis, the first Whig Prime Minister. Many of the radical Crowns criticized his actions of "working with the enemy," but the public and the King admired his open bipartisanship. He oversaw the complete organization of forces in the Pensinular War, and many said that without his work and planning General Winfield Scott could have never won the war (it was also Cass who clamoured to give Scott the command). During his time in the cabinet, Cass became good friends with the Duke, and afterwords they often exchanged correspondense. When Perry became Prime Minister in 1832, Cass requested to remain at his cabinet post, a request Perry denied. Instead, as a "punishment" for working alongside the Whigs, Perry appointed Cass as the Ambasador to France to get him out of the country. Cass again performed ably in this task, and when former French Prime Minister Marquis de Lafayette died in 1834, Cass gave a speech at the funeral in perfect French, amidst much applause. Consistently being informed of the domestic troubles back home, Cass grew more and more frustrated at the direction of the Crown Party. In 1835, he resigned from his position and returned to the URAS. There he began to prepare for a run for the Prime Ministership, supported by the moderate Crown faction, and if he played his cards right, the Whigs. He said he would return the nation to "a country of laws, where ones' right to speech is not punished but respected, and a country where moderation, bipartisanship, and tolerance prevails." Cass had become the leader and the face of what many called the "Constitutionalist Crown" movement. Many Whigs, especially the Duke, saw the chance at hand to tear the Crown Party in two, and get a surefire majority of the people behind Lewis Cass. But many other Whigs distrusted working with the Crowns at all, or compromising their platform. It was with a determined and hopeful outlook that many Whigs entered the convention under a "Draft Cass" banner.

One of the major candidates of course was the Duke of Winterfell himself. Since leaving the office of Prime Minister in 1832, he had become a Minister of Congress and the direct opponent of the Perry administration; he opposed every action Perry made, and had admittingly lost some of his earned popularity for it. But he remained loved by a majority, and respected universally. DeRensis, by law, was now eligible to run again for Prime Minister. If he wanted to run, no Whig would oppose him, and everyone knew this. But he was worried about a possible third term. While he was sure he would defeat Perry, he knew that if he branded the Whig Party directly to his name, that without him as the leader the party would disintigrate. He wanted a party that would stand the test of time, not crumble at the word of his death. But many Whigs didn't share his concern for posterity; they saw that he was still popular with the people, he was trusted, and that he could once again gain the support of Whigs, libertarians, and moderate Crowns from every corner of the country. Privately the Duke was organizing support for a Cass endorsement, although he said publically that if he was nominated, he would run; the country's present state was more important than a party.

Theodore Frelinghuysen, leader of the "Morality Whigs"

While most Whigs had been suffering for the last four years, Theodore Frelinghuysen had had a complete rebound in fortune. Since his election to Congress in 1826 in the Whig landslide of that year, he had become the undisputed moral leader; speaking openly for Christian values, better treatment for the Indians, and a formal opposition to slavery. He condemned everything that he viewed was against the will of God. Originially, many thought he would fail to gain reelection, and didn't take him seriously in his 1832 run for the nomination. But when scandals started appearing in the headlines, suddenly the unquestionably clean record of this political preacher seemed overwhelmingly popular; Frelinghuysen won in a landslide. And since his political rebound, he had been another large critic of the administration in Congress; and more importantly, an untouchable one. He was a key supporter in placing civil service reform at the top of the agenda, and many Whigs thought he would send a good message if nominated; that the Whigs were about ideas, and that Perry was failing to live up to a national standard. But many realists also thought that Frelinghuysen was still just to radical a candidate, and would fail to gain the support of the moderate Crowns. Despite this, Frelinghuysen entered the convention with a sizable and devoted following.

George M. Dallas, Lord Mayor of Philadelphia

Following his 1832 defeat for the nomination, George M. Dallas had continued to serve as the Lord Mayor of Philadelphia, as he had since 1828. He remained fairly popular among moderate Whigs, and had supported the cause by making Perry's life in the capital city a living hell; purposely delaying him on occasions so he arrived late, never once inviting him to a private party, etc. Despite this, Dallas remained friends with the King, and for that reason people thought he could defeat Perry in 1836; not because the people loved him, but because he had King Andrew's ear. But his lack of popular support and a good public perception crippled his chances in this crucial appointment. Many said that out of the candidates, he had the least chance of getting the nomination, but remained a good compromise candidate, and probably had the best odds at getting the nomination of Viceroy if he desired it.

Nominating Convention[]

This year, the Whigs returned to New York City, the site of their 1820 convention. For several days, things remained static, with Frelinghuysen's and Dallas' support going up and down, Cass' name being thrown around the room, and everyone ready to bolt to the Duke if he made a move for the nomination. But on the fourth day, DeRensis gave a prepared speech calling for the Whigs to offically endorse Lewis Cass for Prime Minister. He said the current troubles decended party lines, and that it was no longer "a bitter and frivolous fight between Crown versus Whig, but a moral and basic fight, between absolutism and constitutionalism!" This speech was followed by a few words from Cass, who repeated his promise to run a fair and bipartisan administration, functioning on the basis of law, not party. He also said he would balance the Whig and Crown platforms, and fully support civil service reform. For that, both the Duke and Cass were applauded, and after a few more votes, the Whig convention offically endorsed Cass as their choice for the nominee. When this was decided, Cass made a final speech in front of the convention, stating he would run as a member of the "Unionist Party," built up of moderate Crowns and Whigs, but more importantly of all patriots who loved the union. This left Frelinghuysen and Dallas standing in the cold, but after promises by both the Duke and Cass that they would recieve cabinet positions, they lent their support to the Unionist Party.

What the fight came down to was the question of Viceroy. DeRensis made it clear that he would never again serve as Viceroy, and that he would support the Unionist Party from Congress. Dallas placed his name forth as Viceroy, representing the Whig half of the alliance that was the Unionist Party. With few other choices, Dallas' placement as Viceroy seemed certain. That was until a delegate placed James Barbour name into consideration;

James Barbour, 1836 Viceroy nominee of the Unionist Party

Barbour was also a lifelong Crown member, and had served as a Congressman and Governor of Virginia, before becoming Lord Secretary of the Post under the Duke from 1824-1832. Also known for being bipartisan, Barbour was also a supporter of constitutionalism, and on top of that protectionism and internal improvements; many said that if he wasn't a Virginian, he would have been a Whig. Out of office since 1832, he had avoided getting involved with the Perry administration at all, and after his name was given to the convention, this started a landslide in support for him. It was a very surprised Barbour that recieved a delegation from the convention stating he had been nominated for Viceroy for the Unionist Party (which he of course never heard of), which had also been endorsed by the Whigs. He graciously accepted.

Results[]

The Constitutionalist Crowns, who had been unoffically walking in the wilderness for the past two years, immediately supported the Unionist ticket of Cass and Barbour. Parades of flag-waving Unionists appeared in every section of the country, from Franklin to Cuba. Whigs attacked Perry and the absolutists as perpetual dictators, attempting to enslave the common people, impose their rule at bayonet point, and tear away the rights guaranteed to them. The Constitutional Crowns attacked them as staining the traditional party banner, tearing a rift between the political sections, and creating a police state. While both Whigs and Constitutional Crowns supported the Unionist Party, it was clear that besides Cass and Barbour, all of the so-called Unionists thought of themselves still as either Whig or Crown.

Perry and the remaining Absolutist Crowns went on the defensive. Originially Perry had several pro-Cass demonstrations forcibly ended as "disturbing the peace," but when this continued to turn public opinion against him, he stopped the practice immediately. He claimed he did what was right for King and country, and that he was only taking the power that the government needed to enforce the King's will and keep the country safe from enemies both foreign and domestic. King Andrew remained silent during the campaign, as he had since choosing Perry for the office of Prime Minister.

The final blow came when Viceroy Martin Van Buren, Absolutist Crown and leader of the New York political machine, metaphorically jumped ship. Always the cunning politician, once Van Buren saw which way the wind was blowing, took advantage of the situation. While remaining Viceroy, he dropped his support for Perry and endorsed Cass and a "road of moderation." This gave New York firmly to the Unionists, and Perry's support dwindled from there until only pure absolutists remained. Stunned by Van Buren's betrayal, Perry had him dropped from the reelection ticket. For Viceroy, he was replaced with the Absolutist Governor of Cuba William Trousdale. When it came time for the King to appoint a new Prime Minister, most of the early polls of the day showed Cass at 61% popularity, while Perry only had 33%. Andrew had no choice but to name Lewis Cass the new Prime Minister, and usher in the first "Unionist Prime Minister."

Immediately after taking office, Cass pardoned all people arrested on Perry's orders, and they were retried; most were found innocent. A congressional committee was created to investigate the actions of the previous administration, led by the Duke himself. Many people were called to speak before Congress, and after several months the committee had drawn up all the necessary reports. Former Prime Minister Oliver Hazard Perry was censured by Congress for abusing his power. And former Lord Secretary of the King's Law Levi Woodbury was actually brought to trial and convicted for knowingly not enforcing the Royal Bill of Rights. Although he was quickly pardoned by Cass in a sign of national unity, the damage was done. Perry's political career would end right there, and he was essentially dropped by the Crown Party for losing them so much respect and influence. The investigation found Van Buren completely innocent, and even rewarded by Cass for his political turncoating at such a crucial moment with the appointment of Ambassador to the Commonwealth (while the Commonwealth was one of the prime enemies of the URAS, this position was considered a major one in foreign policy cirlces). With these results, Hunter DeRensis famously quipped shortly after the appointment that, "Now the lion [Perry] is dead; but we must still chase the fox [Van Buren]." The Cass administration would prove to be a very interesting one indeed.